Report

30 Nov 15

“Are poets the unacknowledged bioethicists of the world?” asked Tom Shakespeare, one of our Council members, on Monday night. Quite possibly so, if the rich ideas and concepts put forward by the poets who entered the Council’s (un)natural poetry competition are anything to go by.

Tom was speaking at an evening of poetry and debate that we organised to mark the conclusion of our project on ‘naturalness’. The winners of our poetry competition and Kayo Chingonyi, our poet in residence since the summer, stole the show with their beautifully crafted pieces that explored topics as diverse as organic food, hand transplants, afro hair, mobile technology and emigration.

Sophie Fenella, winner of our (un)natural poetry competition, performing her poem ‘Aubergines in Acton’ in London on 30 November.

In the bar after the event several people asked me "We’re glad you did, but why did you decide to work with poets?" When we started the project earlier this year and got to thinking about how ideas about naturalness affect our views on science and technology, we soon realised this was a subject that resonated with people, and not just philosophers and scientists. When I asked my friends and family if they could define what natural meant, they would launch into a long and interesting debate, usually with no conclusion or consensus. Poetry, we thought, might encourage more people to see our work as something that applies to them. We have involved artists in the Council’s work before, as a way of bringing wider society, particularly young people, into the conversation. There is no question our poets succeeded in this on Monday night, judging by all the young faces in the 100-strong audience. We hope to capitalise on this interest by seeking opportunities for Kayo and our winners to perform in other places in the coming months (please do get in contact if you’re interested in working with us).There was another reason for involving poets. A central focus of the project has been to explore how different people use words like natural, unnatural, pure and synthetic when discussing science and technology – and how language can sometimes hinder communication as well as facilitate it. Who better than to help us unpack words and language in creative ways than poets?

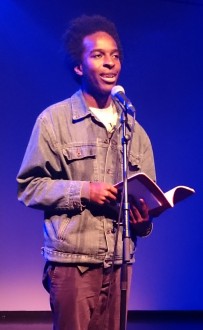

Kayo Chingonyi, poet in residence on the Council's project on naturalness

With the help of the excellent performance poetry organisation Apples and Snakes, we commissioned Kayo Chingonyi to work closely with us for 6 months. His time working with the Council has been both enlightening and enjoyable, on both sides (so he tells me). Kayo brought our attention to the way that language can have the capacity to do things as well as to refer to things. This is a quality that poets regularly draw upon when they write poems that are about something, but also enact something when they are read or spoken. There are parallels with this in the language of naturalness. As one member of the audience pointed out on Monday night, to say “It’s not natural” is both to state your view and shut the conversation down, unless one delves a little deeper into what is meant. Read Kayo’s complete set of poems and his guest blog post that discusses some of these ideas.

We also wanted to encourage the wider poetry community to contribute and, with the help of Apples and Snakes, in September we opened a competition to write a short poem that explored ideas about naturalness. We were surprised and delighted that 152 poets took the time to put pen to paper and enter.

I helped with the tough job of whittling down the entries to a short list of 35. The poems conjured up images of animals (giraffes, ladybirds, ants, hummingbirds, parakeets, pterodactyls, humans) in natural or unnatural environments, behaving naturally and unnaturally. They tackled wind farms, natural disasters, hair removal, cosmetic surgery, child birth, fertility treatment, designer babies, animal-to-human organ transplants, artificial organs, disability, gardening, farming, diet, food, assisted dying, genetic modification, synthetic biology, artificial intelligence and human behaviour – and even that list isn’t exhaustive. The range of topics covered was far wider than those we found in our review of media and parliamentary debates, suggesting that ideas about naturalness crop up far more in our day-to-day conversations than they appear in official public fora.

A theme picked up in many of the poems was the idea that science or the progression of knowledge is somehow battling against nature. Some seemed to suggest that trusting in nature’s ways was the right course of action; often because messing with nature would have dire consequences or was futile given the power of nature to take revenge or bounce back. Some explored the idea of nature as a creation of God, and suggested that unnatural processes or things went against God’s wishes. Some tackled the concept of naturalness in a more abstract way, questioning whether natural always equals good and unnatural always equals bad. Others considered the idea that humans are part of nature and challenged the idea that there is any robust distinction between the natural or unadulterated and the unnatural or man-made.

All these ideas appeared in the different examples of people using the terms natural, unnatural or nature that we found in other aspects of our research. This led to one of the key findings of the project: that many different ideas, associations, anxieties, hopes and fears underlie different people’s uses of these terms. To help organise these ideas more clearly, we set out five broad understandings of nature: neutral/sceptical, wisdom of nature, natural purpose, disgust and monstrosity, and God and religion. Working with poets has validated our view that these different understandings are widespread across the UK public, and showed how exploring bioethics through art can both enrich and widen our discussions. Our huge thanks go to all the poets that took part.

Comments (1)

Isaac

Wow I like this cool :)

jk

Join the conversation